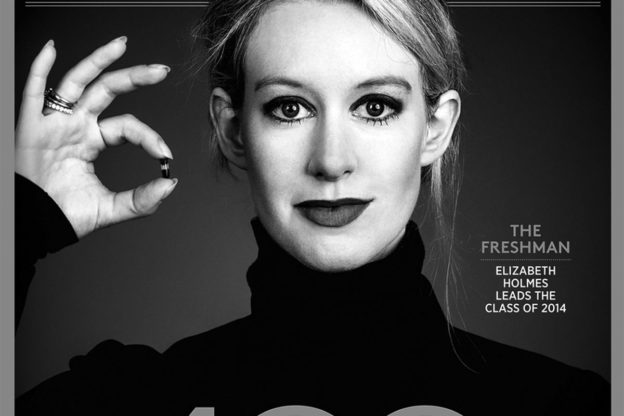

Her start-up became the toast of Silicon Valley, with a $9 billion valuation and a board including former secretaries of state Henry Kissinger and George Shultz. Expanding on his award-winning investigative scoops, Pulitzer-winning Wall Street Journal reporter Carreyrou recounts how Elizabeth Holmes, a charismatic Stanford dropout, started Theranos with claims of a revolutionary blood-testing technology that needed just a few drops from a finger-prick rather than tubefulls drawn from veins with needles. But by the end of the film, in spite of all the revelations about Theranos’ deceptions, she still seems more like a brand than a person.An apparent scientific breakthrough rests on a quicksand of deception in this riveting account of the rise and downfall of notorious biotech firm Theranos. Her stylized image was heavily used to sell Theranos to the public - the idea of a very young woman with a very big idea was core to the company’s model, and to its Apple-esque cult-of-personality approach to advertising. Part of the approach is about considering Holmes’ surface, since it’s so difficult to get past that surface. After that riveting opening, laying out the bare bones of Theranos’ rise and fall, Gibney backs off and spends a long time just on Holmes, exploring barely relevant things like her monochromatic wardrobe (and her insistence that in spite of her admiration of Steve Jobs, she didn’t steal his look - she’s liked black turtlenecks since childhood). The film’s biggest weakness is the way Gibney feints at a larger purpose without really carrying it out.įor viewers not already intimately informed on the Theranos scandal, The Inventor’s first act may seem like a frustrating pile-on of trivia without enough substance to tell the story it teases. But The Inventor doesn’t dig particularly far into that idea, or spend much time contextualizing Theranos in terms of other Silicon Valley startups that have soared or folded. It’s an inherently unstable model that sometimes works, and the rewards if it does can be tremendous. And it implies that the entire structure of the VC world encourages a “fake it ’til you make it” attitude toward technology, with people like Holmes pretending they’ve developed groundbreaking devices, then using the resulting investments to try to bootstrap the technology they claim they’ve already created. It hints that the Silicon Valley startup industry openly encourages companies to lie to investors, and that the lack of regulatory oversight makes it easy for charismatic liars to get away with outsized promises.

There are hints, especially toward the end of The Inventor, that it’s going to explore a wider problem and find larger messages in the Theranos mess.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)